Michael Bennett's departure from the Cleveland Museum of Art reminds us that he appeared to fail to provide the scientific analysis of the bronze Leutwitz Apollo.

Paul Barford wrote some particularly reflective pieces on the issues here.

My own thoughts on the bronze can be found here.

Perhaps the new curator will release the undisclosed studies.

Discussion of the archaeological ethics surrounding the collecting of antiquities and archaeological material.

Monday, 26 February 2018

Saturday, 10 February 2018

History of objects in Virginia exhibition

Colleagues have suggested that I had a look at the exhibition catalogue of The Horse in Ancient Greek Art that will be opening at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA) in a week's time. Among the interesting sources for the objects are:

- Edoardo Almagià: no. 43, Apulian volute-krater attributed to the Virginia Exhibition painter, Fordham University Collection 8.001 [Fordham cat. no. 32]

- Fritz Bürki: no. 19, Apulian lekythos attributed to the Underworld painter, Virginia MFA 81.55; no. 20, Apulian lekythos attributed to the Underworld painter, Virginia MFA 80.162; no. 26, Corinthian skyphos showing a boar hunt, Virginia MFA 80.27; no. 41, Apulian calyx-krater attributed to the Dublin Situlae group, Virginia MFA 81.81; no. 53.1, Apulian Xenon oinochoe, Virginia MFA 81.82; no. 53.2, Apulian Xenon oinochoe, Virginia MFA 81.83

- Sotheby's, London (12–13 December 1983): no. 42, Apulian patera attributed to the Baltimore painter, Fordham University Collection 11.003 [Fordham cat. no. 25].

- Summa Galleries Inc. Beverley Hills: no. 12, a Phrygian terracotta revetment, Virginia MFA 78.62.5. (This looks as if it could be part of the Düver frieze.)

- Robin Symes: no. 55, Villanovan or early Etruscan bronze horse bit, Sidney and Lois Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University 84.28

The series of acquisitions from Fritz Bürki is particularly significant as Dr Christos Tsirogiannis has written on a Gnathian askos acquired by Virginia MFA in 1980. Not only was this acquired from Bürki but it had previously been handled by Giacomo Medici. Has VMFA conducted a rigorous due diligence search on the series of objects that it acquired from Bürki? Has VMFA contacted the Italian authorities about the controversial askos?

Has Fordham University contacted the Italian authorities about the Almagià volute-krater? And what about the Apulian patera that surfaced at Sotheby's, London in 1983?

We should be grateful to Peter Schertz and Nicole Stribling, the editors of the VMFA catalogue, for printing the histories of the objects.

Wednesday, 7 February 2018

ALR: the need to differentiate between looted and stolen

I have been reading the comments made by James Ratcliffe over the return of archaeological material recovered in Europe after being removed from archaeological storage facilities in the Lebanon (Laura Chesters, "Art Loss Register, New York’s district attorney and antiquities dealers team up to safeguard Lebanese sculptures", Antiques Trade Gazette 6 February 2018). The comments relate to material that was derived from the archaeological excavation at Eshmun (see also here).

The two Roman sculptures are given a little history:

- "One sculpture was recovered when an antiquities dealer in Freiburg, Germany, was acquiring it from an Austrian dealer."

- "The second sculpture was identified when a dealer in London contacted the ALR before its potential acquisition. The sculpture was owned by a private collector and ALR contacted US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in New York. The New York County District Attorney’s Office then seized the piece to ensure its return to Lebanon."

Ratcliffe comments:

In principle there is nothing wrong with a trade in antiquities where items have lawfully entered the market, but trading in pieces that are looted is entirely wrong and must stop.The Eshmun pieces were not "looted" from an unknown archaeological site, they were apparently removed from an archaeological store. In spite of the photographic evidence that was available an Austrian dealer and a New York collector were able to acquire these pieces. Were they acquired in "good faith"? Was there anything "unlawful"? How do newly surfaced antiquities "enter" the market?

Ratcliffe continues to misunderstand how the ALR is unlikely to detect recently looted material.

Through due diligence checks it is possible for those in the trade to identify when they are being offered looted material and for it then to be returnedHow will a due diligence check identify looted material? Imagine an Etruscan tomb of the early fifth century BC. No photographs were taken of the objects as they were placed around the body. Now picture the scene of a tombarolo removing the objects from the tomb in, say, 2015. The objects are sold to an intermediary, passed to a dealer in, say, Germany, and then images are sent to the Art Loss Register as part of the due diligence process. The ALR will report back that there is no image in their records, and the dealer can state that the ALR has been consulted. Can looted objects be identified in the process?

I suspect that there needs to be some clarification. Ratcliffe needs to reflect on the ALR's role in the case of the St Louis Mummy Mask, an object recorded from an archaeological site and then apparently removed from an archaeological store.

Friday, 2 February 2018

Ownership of Paestan krater handed back to Italy

|

| Paestan krater. Source: Art Daily |

The Speed Art Museum in Louisville, Kentucky has agreed to transfer ownership of a Paestan calyx-krater to the Italian authorities ("The Speed Art Museum and Italian Ministry reach loan agreement on ancient calyx-krater", Art Daily 2018). It will, however, remain on loan in the museum. The krater, showing Dionysos playing the sympotic game of kottabos, was acquired in 1990 from Robin Symes (inv. 90.7).

It appears that the krater was identified by Dr Christos Tsirogiannis in 2015 from images in both the Medici Dossier and the Schinousa archive. Symes had claimed that the krater had come from a private collector in Paris.

This is one of a series of Paestan objects that have been returned to Italy. They include the Asteas krater from the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Paestan krater from New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art, a Paestan squat lekythos from the Fleischman collection, a Paestan squat lekythos from a Manhattan gallery, and the Paestan funerary painting.

The fact that the Speed Art Museum has responded to these concerns is encouraging. Stephen Reily commented on the "shared interest in the responsible celebration of Italian cultural heritage".

One wonders if the Michael C. Carlos Museum will also be responding to the identification of objects in its collection from the Becchina archive.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

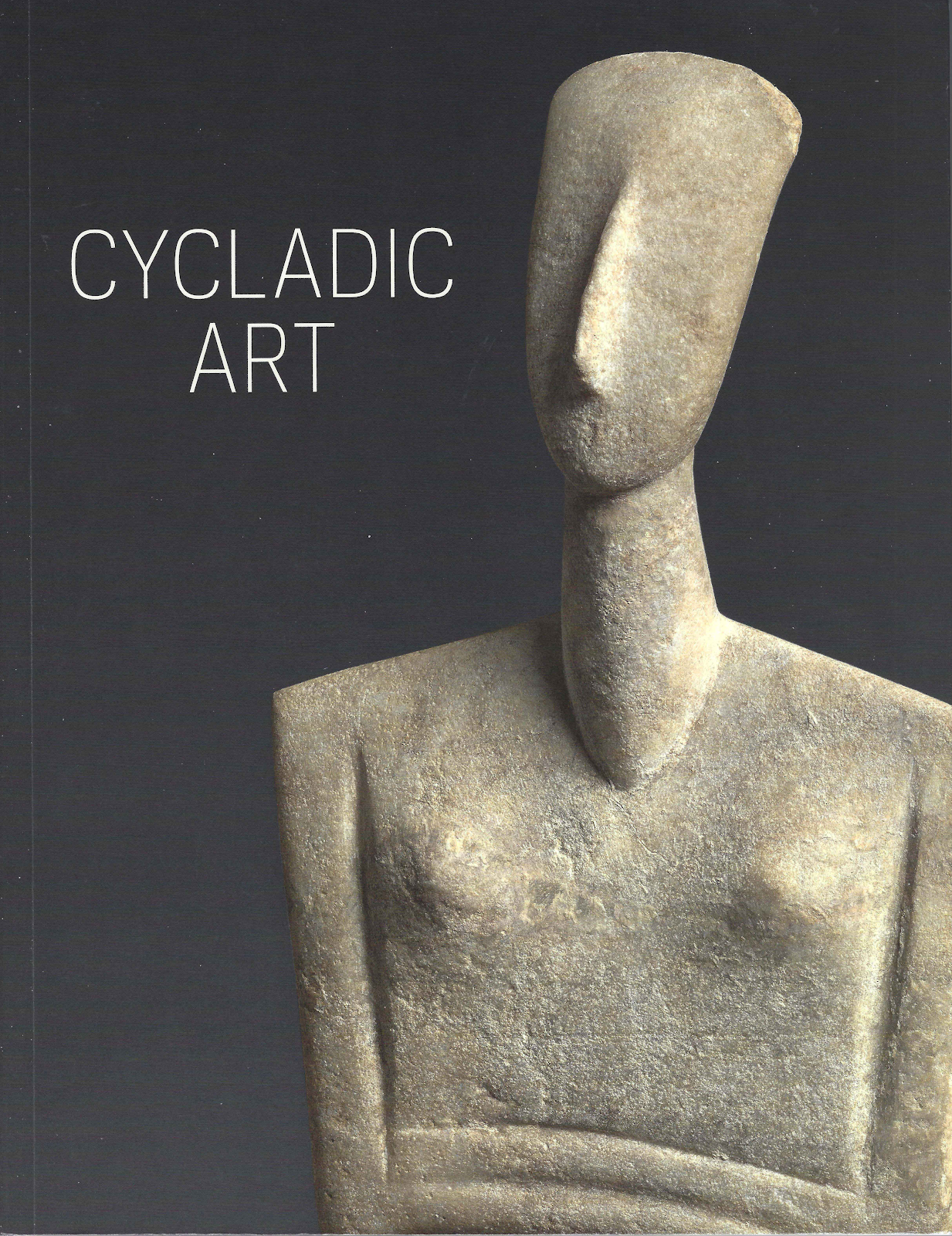

The Stern Collection of Cycladicising Figures

My review article on the Stern collection of Cycladicising figures currently on display at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art has bee...

-

Source: Sotheby's A marble head of Alexander the Great has been seized in New York (reported in " Judge Orders Return of Ancien...

-

If international museums can no longer "own" antiquities either through purchase on the antiquities market or through partage , wh...

-

The Fire of Hephaistos exhibition included "seven bronzes ... that have been linked to the Bubon cache of imperial statues" (p. 1...